“True elegance is in the head. If you have that, the rest will follow.” Diana Vreeland, famous American fashion journalist.

The big fashion houses will confirm it to you, an idea can bring in a lot of money. They will specify that a prying eye or a well-hung tongue is enough to reduce months of investment to nothing.

In an economy as competitive as ours, the question of the valorization of ideas, developed to become "intellectual creations", has quickly arisen. It will be admitted that the time spent building a collection is difficult to make profitable, since a competitor has the right to copy these creations with complete freedom.

Intellectual property law is a branch of law that grants exclusive rights to an author for his book, to an engineer for his invention or to a company for its brand: it offers the creator a monopoly limited in time. on the exploitation and management of its creation .

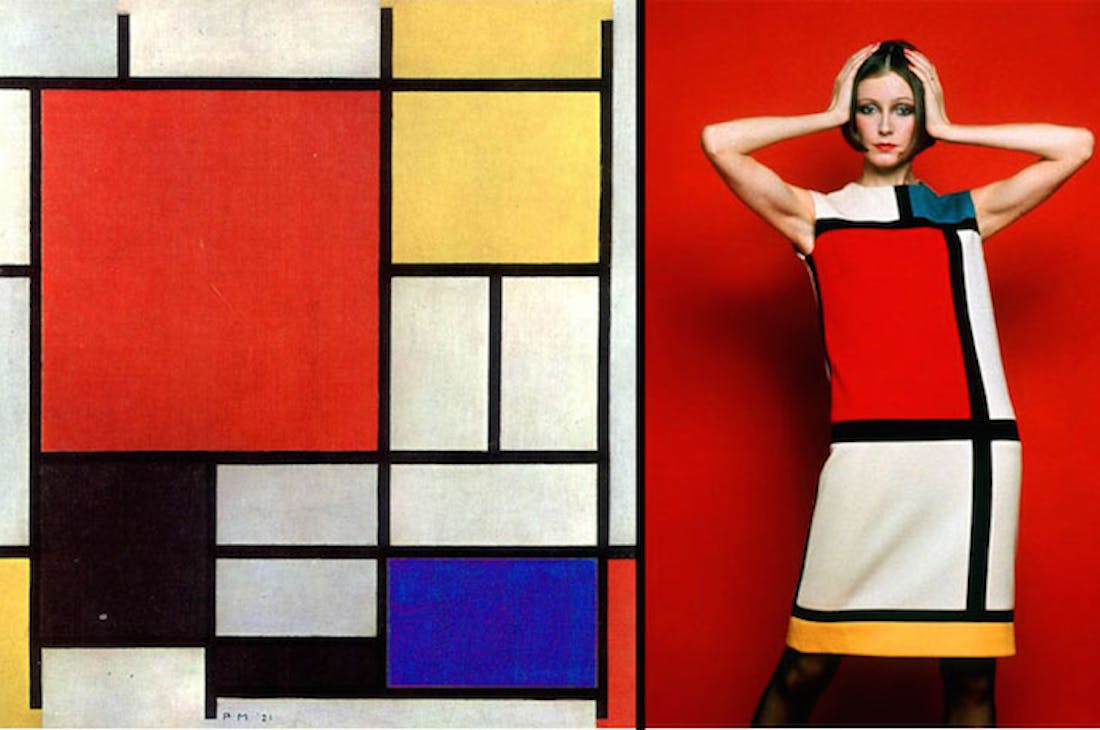

The genius of Yves Saint Laurent in action.

Disclaimer: A loyal reader of BonneGueule, Bertrand is a law student. Passionate about intellectual property issues, he wanted to contribute to our columns to explain this often opaque subject. The floor is his!

A bit of history...

Already in the 6th century BC, the inhabitants of the Greek colony of Sybaris granted cooks a monopoly on anyone who could divulge their cooking recipe to the public. Everyone won: cooks were encouraged to innovate and sybarites enjoyed themselves.

At the same time, craftsmen adorned their pottery with rudimentary marks. These few signs were intended to reassure the consumer about the origin of the product and to avoid counterfeiting, that is to say reproductions suggesting that the product is authentic.

But it was during the Italian Renaissance that these first steps find a real legal resonance. The Italian architect Filippo Brunelleschi obtained in 1421 one of the first patents in History during the construction of the famous "Duomo" of Florence.

The sumptuous “Duomo” of Florence… breathtaking!

Large quantities of marble were transported by the Arno, the river that ran through the Florentine city. Brunelleschi then invented a barge capable of transporting the large quantities of marble needed to build the Duomo. In exchange for this invention, the inventor was granted exclusive rights to its exploitation.

Venice would follow Florence's example fifty-three years later by promulgating the "Parte Veneziana", a law establishing a ten-year monopoly for the creator of a new invention, useful to the community and in working order. This unprecedented policy offered the Serenissima a remarkable concentration of artisans and engineers, who would participate in its commercial influence throughout Europe.

Intellectual property thus appears as the ideal means to protect intellectual creation against copying . Its objective is to create a virtuous circle, encouraging society to invest time and capital in new artistic or industrial projects. .

What about today?

Our system of intellectual property protection developed massively during the 19th century. It is divided into two branches:

- on the one hand, the protection of literary and artistic works , granted in particular to artists or software programmers;

- on the other hand, the protection of industrial creations , protecting brands, inventions, designs and models or even our very dear AOP/AOC.

AOP-AOC, official partners of your aperitif.

So there are a number of ways we can protect our intellectual property. Now that we have the broad outlines, let's go into more detail by looking at the specific field of fashion, starting with designs.

Designs and models: the most obvious protection

Protection of the design of a product

The design regime is designed to protect the external appearance of a product or part of a product. This could be a screen print on a T-shirt, the shape of Pharrell Williams' hat or the case of a smartphone.

We speak of a drawing when the object to be protected is represented in 2D (for example, screen printing); of a model when it is represented in 3D (here, the hat).

Here, a model-that-hurts-when-you-step-on-it.

Among the legal options available to the textile industry, this protection is a priori the most suitable: the shapes, cuts or textures of the clothing are directly concerned.

To obtain this protection, a deposit must be made for each design or model with the National Institute of Intellectual Property (INPI), or its European counterpart, the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO).

Once the design or model has been filed, it is necessary to request an extension every five years for it to be maintained, the total duration of protection not being able to exceed twenty-five years.

If you have the opportunity to go to the INPI headquarters, the premises are rather nice.

And in practice?

The rapid cycle of collections, however, makes this deposit unsuitable for most items sold. A simplified deposit system has therefore been provided for by Article L512-2 of the Intellectual Property Code "for designs or models relating to industries which frequently renew the form (...) of their products".

This article obviously concerns the fashion and clothing industry. It offers the possibility of only summarily protecting the entire collection, then covering a posteriori the flagship models that have made an impression and therefore risk being widely copied.

In addition, within the European Union there is a special regime for "unregistered" designs, for a short period of three years from the disclosure of the object on European territory. This special protection does not require a deposit; certainly the duration of this protection is shorter, but it is ultimately a good compromise in terms of fashion, the regime then being closer to that of copyright.

What about copyright?

The author, protected by the sole fact of his creation

Copyright protects “works of the mind,” that is, literary works, paintings, or even cinematographic works.

New Hollywood or New Wave, same issues, same rights.

It has the immense advantage of not requiring any formality, the work being protected by the sole fact of creation . It would therefore be illegal for an Internet user to take this article and copy it into his blog without my permission.

Fashion protection by copyright

At first glance, it might seem surprising to describe a garment as a work of art, even though it is a utilitarian object. American copyright law makes a distinction between works of the mind (paintings, sculptures, books) that can be protected under this regime, and "utilitarian" items (chairs, lamps, clothing) that cannot be protected.

However, French law refuses to make such a distinction and expressly cites fashion as an object covered by copyright in Article L.112-2 of the Intellectual Property Code. The design or model regime and that of copyright can therefore be combined.

The main problem then concerns a criterion specific to copyright, that of originality. If its rights are contested, the fashion house may have to demonstrate before the judge the originality of its creation, that is to say the imprint of the personality of the designer.

A simple plaid shirt or a pair of raw jeans cannot therefore be protected by copyright. But if originality is demonstrated, the author is recognized as having patrimonial and moral rights over his work.

At first glance, this Éditions MR coat (left) is original, even if it is undoubtedly inspired by the regatta blazer worn by Alain Delon in Plein Soleil (right). Conversely, the turtleneck is certainly not: it is a basic that does not reflect the imprint of the author's personality.

“Long-lasting” protection

Copyright is dual: it consists of moral rights and property rights. While moral rights ensure respect or authorship of the work, it is property rights that are of most interest to fashion companies: they allow the authorisation or not of the representation, then the reproduction of the work.

These are the rights that are generally transferred for remuneration, and which allow you to receive what are commonly called “copyrights” or “royalties”. In practice, the fashion industry often uses copyright, in addition to the classic designs regime.

The first reason, specified above, is that copyright has the advantage of not requiring any deposit: protection costs will therefore only arise in the event of a dispute. Then, the duration of protection is particularly long: initially, the author will have this protection until the end of his life, then until 70 years after his death, his beneficiaries will benefit from the economic rights.

Created in 1935, the Hermès “Kelly” bag is still a must-have. The design regime no longer applies, but its creator Robert Dumas died less than 70 years ago (in 1978). Copyright therefore takes over, until 2048.

Not forgetting trademark law!

Dior, Lacoste, Commune de Paris: whether it is a big name in fashion or a "small" designer from the Marais, trademark law is, among the range of rights that intellectual property includes, the most useful for companies in this sector.

This system allows a company to protect a distinctive sign , which will allow it to distinguish its products and services from those of another company. The trademark is, like designs and models, subject to a deposit with the INPI or the EUIPO. Trademark law has the immense advantage of being perpetual, provided that a fee is paid every 10 years to keep it in force.

Again, this is the logic at work: a brand can stand the test of time and it would be problematic for Coca-Cola to lose its rights to its brand because of its age and success.

The Coca Cola brand has been around since 1886. Because we told you it's vintage!

The range of what can be considered a trademark is very broad: a name, a logo, a color are all signs that can be protected . It must nevertheless be limited to a particular category of products. . The INPI, and then the judge in the event of a dispute, must nevertheless verify a set of criteria, in particular its distinctive character: establish that it is neither a generic sign , nor of a descriptive sign.

For example, signs such as "the beautiful coat" or "the leather shoes" would certainly be recognized as descriptive, and could not constitute a trademark as such.

Putting Intellectual Property into Practice

The fight against copying

Generally, fashion houses prefer to keep their next creations secret and rely on confidentiality until their disclosure to the public, rather than registering traditional designs. The regimes of trademark law, copyright or design law take over a posteriori, in the event of a dispute. .

What about foreign counterfeits?

These rights have a territorial dimension, which means that each State has its own intellectual property law. .

The “Lacoste” crocodile, the most abused reptile in the world.

This territorial nature poses a problem in international trade, which is why conventions have been signed by almost all the States of the world in order to determine which law is applicable to each international dispute in this area.

The final word: from Mondrian to Saint Laurent

These protection methods, which concern the vast majority of our everyday objects, are therefore cumulative. To illustrate this, I suggest we analyze the case of the Mondrian dress, reproduced above:

On the left, a dress from Yves Saint Laurent's "Homage to Mondrian" collection (1965). On the right, "Composition C No. III in Red, Yellow, Blue and Black" by Piet Mondrian (1935).

- First of all, Piet Mondrian's rights holders certainly granted Yves Saint Laurent permission, under copyright law, to enable him to trace the work in this way.

- The dress was then able to be protected as such under the design and copyright regime.

- Finally, the term “Yves Saint Laurent” is protected by the trademark law regime.

And that is the genius of such a complete palette: if "fashion is for France what the gold mines of Peru are for Spain" , intellectual property often knows how to deliver the blow that counterfeiting deserves. Even if this effort is sometimes insufficient, it at least has the merit of doing everything possible to protect this national gem.